Chimeric Visions: Imagining Hybrid Lifeforms

2019

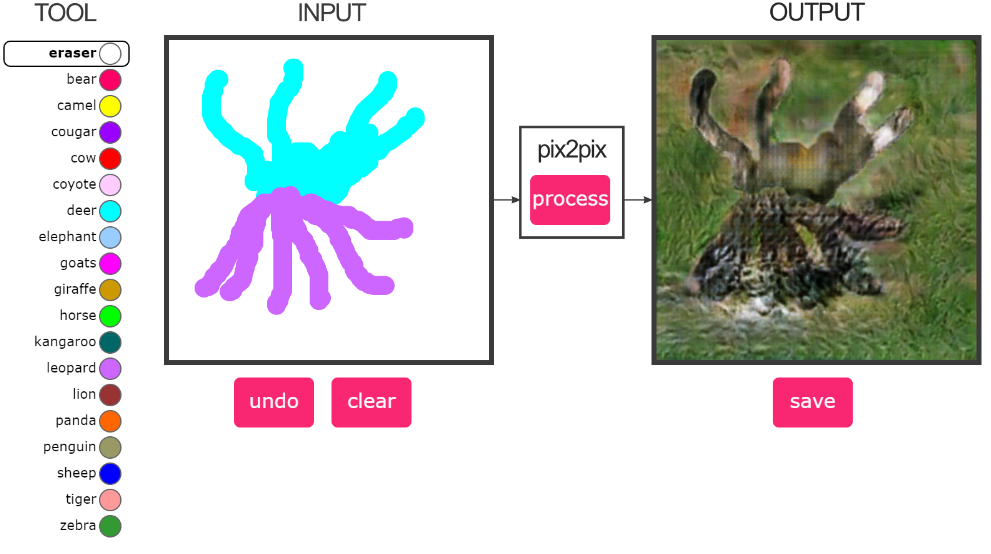

This experiment explores how hybrid lifeforms can take shape through a dialogue between human gesture and machine interpretation. Custom Pix2Pix-trained animal brushes produce species-like forms as each stroke is made; hybrids emerge through the layering and switching of these brushes, allowing new anatomies to surface through intention, revision, and the model’s own learned patterns.

Built on Christopher Hesse’s Pix2Pix framework, each brush draws on segmented datasets that encode the textures and contours of different animals. The project works within the practical limits of training data, resolution, and environment setup, letting these conditions shape the visual character of the results. It raises questions about how generative systems extend, simplify, or reinterpret the structures they learn. These studies point toward further possibilities: brushes with richer anatomical cues, human–animal–machine combinations, and more responsive interfaces that give user gestures a clearer influence on how hybrids form—balancing deliberate control with the model’s capacity for unexpected variation.

SELECT EXPERIMENTAL OUTPUTS

Left: sheep-cougar hybrid, right: goat-camel hybrid

Left: deer-cougar-penguin creature, right: camel-deer-bear-kangaroo-panda hybrid? (user contribution)

Left: panda-penguin hybrid, right: bear-leopard hybrid

PROCESS

Hybrid creatures have appeared across cultures for centuries, embodying our ongoing fascination with imagined lifeforms. This project began as an exploration into how simple gestural drawings could be transformed into composite anatomies—merging human and animal features through a system of species-specific brushes.

Assembly based creativity in 3D

GANDissect style human body segmentation

Body dissection & reconfiguration

Explorations on potential methods

To build the tool, a series of Pix2Pix GAN models were trained—each corresponding to a different animal—so that a chosen brush would generate characteristic textures and forms as the user drew. Developing these models involved navigating the practical realities of machine-learning workflows: dataset preparation, segmentation formats, environment compatibility, and the challenges of running long, GPU-intensive training sessions. The process of tuning dependencies, configuring CUDA environments, and stabilizing training shaped both the system’s behavior and the aesthetic range of the resulting hybrids.

DATASET COLLECTION & MANIPULATION

KTH-ANIMALS dataset (2008)

Auto-cropping generally resulted in important information being lost – in this case, the giraffe’s head

The KTH-ANIMALS dataset formed the base of the study—roughly 1,500 images across nineteen species, each paired with a hand-segmented mask. A custom batch script extracted the foreground shapes, revealing the slight pixel-value variations hidden within the dataset’s nearly black PNG masks.

As an exploratory proof of concept, the project was guided by what the data made possible. Human–animal combinations were considered, but suitable datasets of unclothed human figures were limited, and most animal datasets lacked detailed pose or skeletal annotations. Pose-estimation tools such as DeepLabCut and LEAP pointed toward more granular possibilities, though the extensive annotation they require placed them outside the scope of this early stage.

Pix2Pix’s fixed 256×256 format introduced additional constraints. Many source images arrived in different resolutions, proportions, and orientations, and reducing them to a single size often trimmed away defining anatomical regions. Experiments with seam carving and mask-aware cropping attempted to preserve more of each figure, while object-recognition tools such as Detectron were explored as ways of building more consistent masks in future iterations.

TRAINING PROCESS

The model was trained for 200 epochs on a Windows desktop with an i7 processor and an Nvidia GeForce GTX 1060 GPU—modest but sufficient for this proof-of-concept. Several TensorFlow and CUDA configurations were tested before a stable Pix2Pix-TensorFlow setup was found . On CPU, the network managed only thirty epochs in over twelve hours; with GPU acceleration, it completed the full 200-epoch training in roughly the same span.

Because the original Pix2Pix code triggered security flags on multiple machines, the codebase was reworked and the model exported through Google Colab instead. The training process became a kind of record—cycles of trial and error that made the model’s learning visible as it gradually improved at reconstructing the textures and contours of each species.

input output target input output target

very initial results

Testing shows it works well with some animals more than others

DISCUSSION

Pix2Pix captured the broader structure of each animal—the silhouette, the posture, the basic texture—but the finer points rarely survived the translation. Faces blurred, paws collapsed into simple shapes, and the small markers that make a species distinct were often lost. More granular, part-based or pose-level annotations would help the model preserve these finer anatomical structures and enable more intentional human–animal hybrids.

The fixed 256×256 resolution also imposed noticeable limits. The training images came in many shapes, orientations, and resolutions, and reducing them to a single size often cut away defining regions or compressed the body in unintended ways. These distortions directly influenced what the model could reconstruct, pointing toward the need for more adaptive preprocessing in future iterations.

The background reconstruction produced some of the more unexpected behavior. Because the backgrounds remained in the training data, the model developed a tendency to blend mask structure with whatever environmental traces were still present, creating images where figure and ground were not entirely separate. In scenes with multiple masks, the lack of distinction between them added a further ambiguity and sometimes led the model to merge several animals into a single composite form. Training a version with differentiated masks would offer a clearer view of how the model behaves when that ambiguity is removed, and what remains of this behavior once that ambiguity is taken away.

IDEAS FOR EXPANSION

Future explorations could broaden both the technical vocabulary and the expressive range of these hybrids. Architectures such as CycleGAN may offer alternative ways of transforming line-based inputs, while a more curated animal dataset with context-aware cropping could improve sensitivity to contour and proportion. Filtering and selective image choices could also push the outputs toward more sketch-like or drawing-inspired forms.

A more flexible interface—gesture-responsive brushes, adjustable stroke widths, and augmented filters—would give user input a clearer role in shaping each hybrid. Expanding the taxonomy to include human figures or mechanical components, guided by pose-estimation data, could enable combinations that are more intentional and anatomically legible.

Together, these directions point toward a system in which form emerges from the negotiation between human gesture and machine inference, shaped by the constraints and possibilities each brings.